TMI about my vaginal breech birth in Norway

So this is how we continue the human race. All right.

- Oct 21, 2022

- Comments

Hello, reader! Before you delve into this long-ass post, I want to emphasize that my experience is just one of an unlimited number of way things can go during labor. I don’t know how representative my experience is of birth, breech or otherwise, in Norway. And I’m no expert on anything medical- or science-related, which will become exceedingly clear when you read my post. I just wanted to write something somewhat informative and amusing. And draw silly doodles. Enjoy the post!

I hope one day Tilda asks me what I was doing when my water broke. Think of the valuable insight she’d gain into the woman who gave her life. What words could I say to inspire her, to show her how greatly I anticipated her arrival? Maybe I’d reply with something like this:

“I was taking a Buzzfeed quiz on my phone while lying in bed. I wasn’t tired, but, eh, I was too lazy to roll out of there. It’s possible I had to pee. But the bed was too comfortable, and I just…”

As I continued blabbering, Future Tilda would look at her screen featuring a homework assignment titled, “My Mom, My Hero”. Then she’d jab the backspace key with the cadence of a leaky faucet, taking her sweet time deleting each letter until her document was unsoiled, unlike her feelings towards her mom.

Should I have been doing more to prepare for the arrival of my firstborn child? Probs. Was I too relaxed as a shadow of responsibilities loomed over me and rasped in my ear, “Heeey, I’m right behind you”? Mebbes. Did I even know how to hold a baby? Nopes. But I had already spent the previous few weeks worrying that I could go into labor at any moment, and all that gave me was stress and not a baby. Seeing as I was still two weeks away from my due date, I figured I had plenty of time to go into labor and/or freak out. So I stopped worrying about labor and I focused on the task at hand: challenging an online quiz to guess my age based on my dessert preferences. (You guessed wrong, Buzzfeed! Hahahahaha, surely you are devastated.)

Then I felt a movement in my belly, accompanied by a faint pop sensation. That’s an interesting kick, I thought. Probably nothing out of the ordinary. I wonder how Tilda is do—AAHHHH AHAHHHRGGG AHGGHUUHHFHFH FLUID EVERYWHERE FUFUUHHHHH SO WARM, SO UNCONTROLLABLY FLOWING OUT OF ME, SO EVERYWHERE.

So that’s what it feels like when your water breaks. Like a hose someone tossed on the lawn and forgot about mid-watering. Cool. I mentally cursed every TV show and movie character who’s reacted to their water breaking like, “[light gasp] My water broke!” While searching for a montage of water breaking scenes, I came across Birthly TV, a channel that collects clips of birth scenes from movies and TV shows from different countries. So if you’re curious about that, there it is. As for me, just looking at the thumbnails increases my blood pressure. ;_; Did you suddenly remember you only have two glugs of milk left in the fridge and you forgot to buy more? Or are you having a baby?

After what was probably just a few minutes but felt much longer thanks to my brain stretching out each minute like time dilation Silly Putty, things slowed down to a dribble. Enough fluid seemed to have escaped that I imagined Tilda was lying in a dried-up sac, unknowingly waiting for death. If you’re worried about this happening to you too, though, you shouldn’t—flood-level water breakage before the start of labor is not the norm. It’s more likely for your water to break after labor has started, and even then it could just be a trickle. Hell, your water might not break on its own at all, resulting in your sac needing a good ol’ pokety poke. As for why I ended up with the forgotten hose of amniotic fluid, I don’t know. Maybe it was due to Tilda’s breech position or her scrawny weight of just five pounds, barely more than the heaviest preemie. But maybe I just won the amniotic fluid jackpot.

I had only found out a week earlier that Tilda was in the breech position, aka butt- or feet-down, aka the wrong way. My midwife had scheduled an extra ultrasound for me due to her concern that Tilda was underweight. The ultrasound revealed not only that she was smaller than average, but that she was also in the breech position. By the end of the week, I had gotten an MRI scan of my pelvis to determine whether I could give birth vaginally. The morning I went into labor, I was supposed to have an appointment at the hospital to go over the results of the scan and figure out the best way to get Tilda out of me.

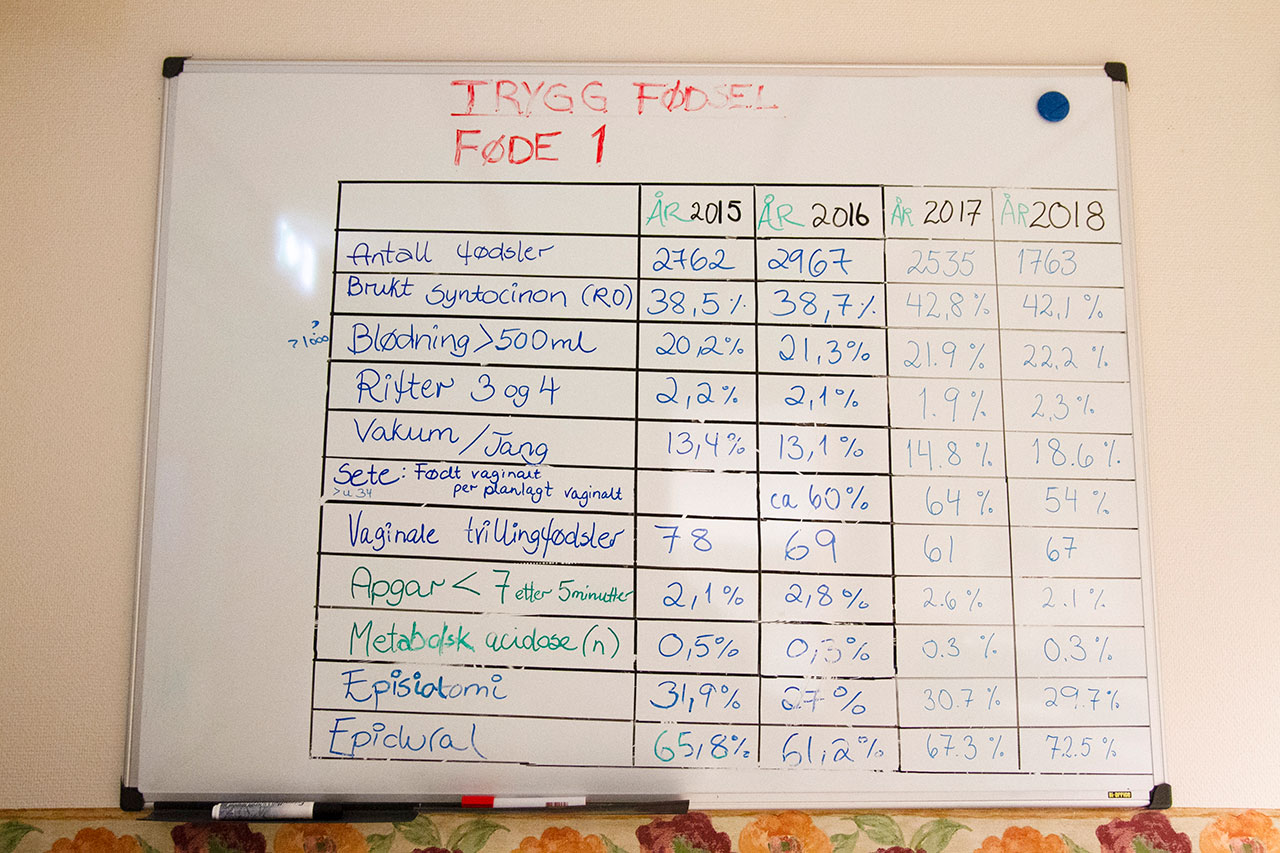

Quick reader survey/test of my ignorance: Did you know vaginal breech birth was a thing? Until my midwife mentioned it, I, uh, did not. I had assumed that if a baby couldn’t be turned around manually, they would be delivered by caesarean section. Maybe my ignorance could be forgiven since I’m from the U.S., where vaginal breech births are uncommon and C-section rates are high. How uncommon are vaginal breech births? Here’s some data I found while falling down a Google hole, presented to you in this mess of a footnote. In 2019, 6.2 percent of the 150,678 breech babies born in the U.S. were delivered vaginally, with the other 93.8 percent delivered by C-section, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data presented by Evidence Based Birth. During the same year in Norway, 33.8 percent of the 2,547 breech babies born were delivered vaginally and 66.2 percent were delivered by C-section, according to medisink fødselsregister data presented by Norsk Helseinformatikk. Of course, Norway has a far smaller population than the US, but their approach to breech births and health care in general is very different. There’s more data in this article from the May 2016 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology on the decrease of vaginal breech births in the US between 1999 and 2013. Also check out this Elle article from May 2017 where contributor Courtney Doggart gives more background info on the decline of vaginal breech births and recounts her struggle to avoid a breech birth by C-section in NYC. In 2020, the year I gave birth, 15.8 percent of births in Norway were delivered by C-section, according to Folkehelseinstituttet, versus 31.8 percent of births in the U.S., according to CDC. As for why the C-section rate is so high in the U.S., there’s a ton of information out there that I’m too lazy to summarize but you should check out. Since I didn’t want a C-section, I’m grateful that the health care system here pushes hard (pun not intended nor regretted) for vaginal breech birth. I wouldn’t blame anyone for preferring a C-section though, especially when carrying a baby in the breech position.

As soon as I thought my amniotic fluid had stopped flowing out—I didn’t yet know that you just keep on dribbling until you give birth because no one tells you these things, why—I grabbed my phone and scurried to the bathroom, trying not to leave a trail of sac drippings. While sitting on the toilet with a false sense of calm, I called Kåre as he was at work delivering mail.

“My water broke.”

“Oh!…should I leave work soon? Or after my second route?”

“Uh…I dunno.”

That’s not exactly how the conversation went, but that’s the only part I can remember. Channeling all our brainpower into speaking with a false sense of calm probably muffled some brain cells.

After I got off the phone and put on what I hoped was an adequately absorbent period pad, I tore all the sheets off the bed and shoved them in the washing machine. I didn’t think Kåre needed to see what the bed would look like if an incontinent hippo had slept in it. He’d have plenty of horrors to see in the coming days. In the meantime, Kåre called his parents, Arne and Aslaug, and asked them to pick me up and bring me to the hospital.

Next, I called Kvinneklinniken’s admissions hotline for peeps who have gone into labor or are on the cusp. Kvinneklinniken is the women’s clinic at Bergen’s main public hospital, Haukeland sjukehus. If you’re planning to have a baby in Bergen, you’re probably going to give birth at Kvinneklinniken. After telling the operator that my water had broken but contractions hadn’t started, she told me to come in as soon as I could due to my complication of having a baby in the breech position.

While I waited for Kåre’s parents to arrive, my brain played a scrolling LED display with something like this: everything is fine but something might be wrong but everything is fine but something might be wrong but everything is fine… In my mind, each passing second brought Tilda closer to death-by-shriveling-sac. When my mother-in-law, Aslaug, showed up at the front door, my anxiety level dropped to something far less heart attack-y. Both of my parents live on different continents from me and each other, so being just a half-hour drive away from my in-laws is a huge blessing.

I’m also lucky to live so close to Haukeland, a medical institution so massive that it feels like its own little city. It’s five minutes away by car, 30 minutes by foot. If I hadn’t been dripping amniotic fluid, I could’ve waddled over. After my father-in-law, Arne, dropped Aslaug and me off, I headed straight to the receptionist in poliklinikken (the outpatient section) to check in. “Checking in” didn’t involve much more than telling the receptionist my name. No paperwork, no insurance cards, just a variation of, “Hi, I’m Robyn Lee, I called earlier because my baby sac uncorked itself.” If you’re a resident or citizen of Norway, you’re part of the national health care system where pretty much everything is digitized and nearly all pregnancy-related treatment is free. I should clarify that adults usually pay a copayment (egenandel) for public health services until they reach their yearly deductible, but most pregnancy-related treatment is free. Public health services for kids are also free, including dental. I don’t know the extent of what is or isn’t covered by the national health care system, but from my experience it’s easy to navigate and get the treatment you need. My mind is constantly blown by how straightforward the system is after coming from the U.S., whose system I will never fully understand. If I ever feel a longing to move back to the U.S., I’ll just rewatch “A terrible guide to the terrible terminology of U.S. Health Insurance” by Brian David Gilbert. Poof, longing obliterated! (I know you don’t want to watch a half-hour-long YouTube video, but it really is worth every second of your bewilderment/despair.) Which is how it should be everywhere, right? Oh well.

After a bit of a wait that allowed me to hone my thoughts about Tilda in her shriveling amniotic sac, a midwife accompanied by two students gave me a check-up in a private examination room. The midwife, after conducting some belly pokery (the specifics of which I don’t remember, so “belly pokery” it is), concluded that everything looked good. My vision of Tilda flopping and gasping about like a doomed goldfish abated.

On my way out, the midwife handed me an incontinence pad and a pair of mesh underwear. This was it. My initiation into the Labor Club. I was happy to switch to an XXL-sized pad that was far better at accommodating the amniotic fluid that kept on coming, stuffed into a much more comfortable crotch net that made me feel like a coddled Asian pear.

Next, I went to the nearby electronic fetal monitor (EFM) room to get my heart rate and Tilda’s heart rate monitored, as well as my contractions. The tending midwife put an incontinence mat on the La-Z-Boy-like seat as a precaution before strapping me in. It made me think about when I take out the garbage, I sometimes stick the garbage bag into another bag if it’s especially bulgy and I’m afraid it could spring a leak. That was meee! Bulging and susceptible to leaking! Being pregnant is so very fun.

While I was hooked up to the EFM machine, Kåre showed up, still in his work clothes. A while later, a doctor came in to tell us that my next stop would be a delivery room. Even though I hadn’t gone into labor yet, they wanted to admit me right away and monitor me due to a potentially complicated birth. Otherwise, they probably would’ve sent me back home to wait until my contractions started. After my tests were deemed normal, we went back to the waiting area.

And now we wait: 13 hours until contractions begin, one day until birth

From the waiting area, we were led to a room in Føde A, one of the hospital’s three birthing wards. The two main wards, Føde A and B, are equipped to handle all kind of pregnancies, low to high risk. The third ward, Føde C Storken, is just for low risk pregnancies. Never having been in a delivery room before, I was surprised by how large it was. There was plenty of space for all the roller skating I wasn’t going to do, and more importantly, all the medical equipment and personnel I might need. Right across the hall was the shared patient bathroom and shower, a comfortably sized space that was more recently renovated than the delivery room. Best of all, it featured [cue angelic choir] an endless supply of mesh underwear and incontinence pads.

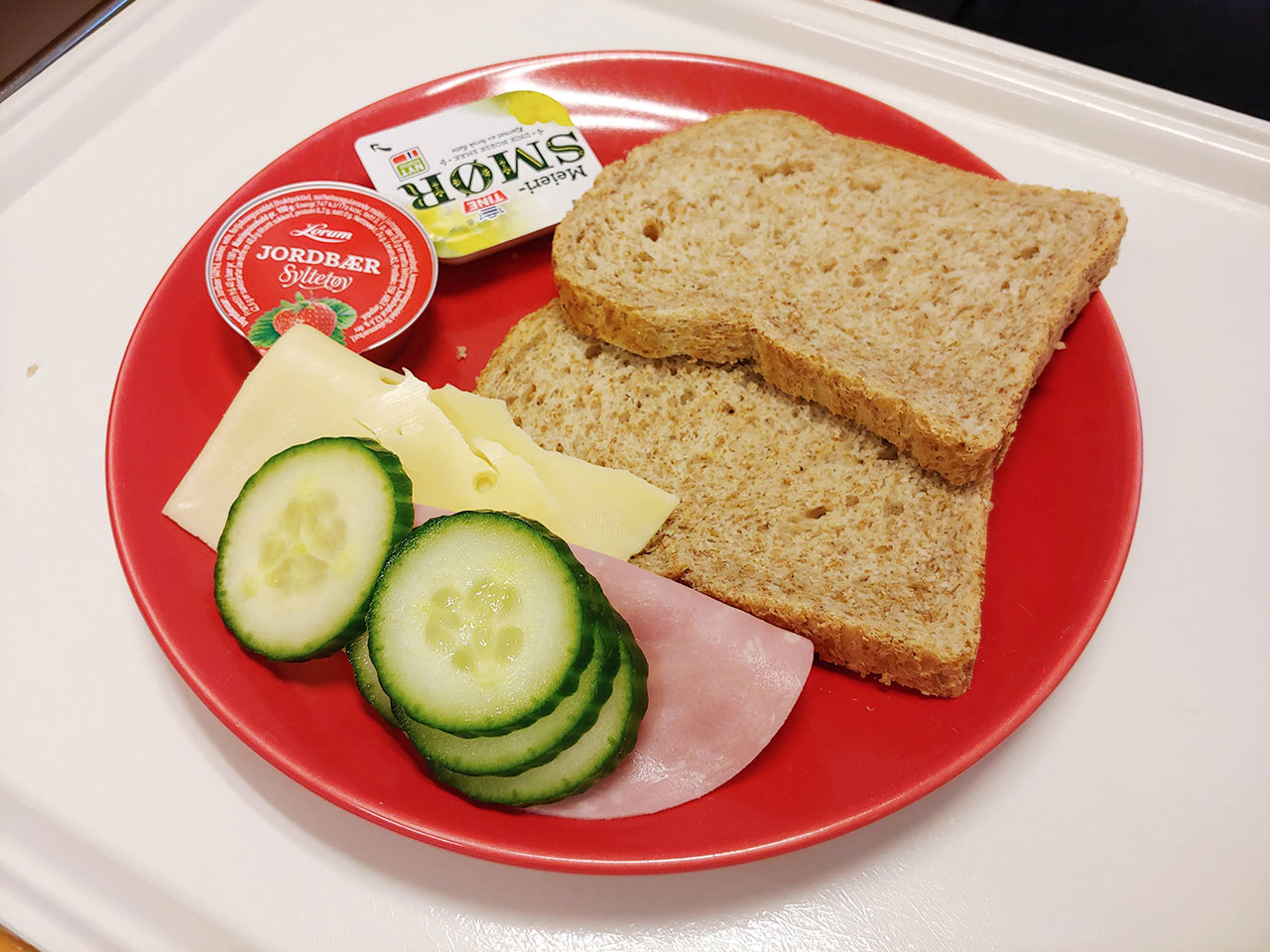

A midwife soon came in to check on us. By this point it was close to 2 p.m. and the only food I had eaten that day was a raisin bun Kåre had brought me. I didn’t feel that hungry, probably because all the I need calories? To function? thoughts in my brain were being smothered by the I’m having a baby real soon? Out of my vagina? thoughts. I definitely needed food. The midwife put together a snack for me, the standard Norwegian combo of brødskiver (slices of bread) and pålegg (stuff that goes on bread—cheese, meat, spreads, etc). As the patient, I was entitled to as much free food as I wanted, while Kåre had to supply his own meals (but if the partner looks like they’re on the verge of starvation, I doubt they’ll be denied).

A while later, a different doctor than the one we had met in the EFM room came in to talk to us about the game plan for “Operation: Get Baby Out of Me (Ideally Without an Actual Operation)”. If I didn’t start having contractions within 24 hours of my water breaking, she told us they would induce a vaginal breech birth. What about a C-section? They’d do it if necessary, but the results from my pelvic scan showed that I could do a breech birth. Would I get an epidural? Almost certainly. Episiotomy? Probably. Enema? Optional but recommended. Would forceps be used? Maybe. When the time came to push, a small army would come to my room to make sure everything went smoothly: two doctors, two student midwives, and another four or so midwives. (This is where the personal roller-rink size of my room came in handy.) If there were awards for good bedside manner, this doctor would’ve won all of them. She was incredibly calming and reassuring, filling me with confidence that everything would go okay even though this was my first time giving birth and we didn’t know exactly how things would pan out.

Once upon a time—about two weeks before I was sitting in that hospital room, before I knew Tilda was in the breech position—I had written a birth plan. After the doctor gave us a rundown of the delivery procedure, I mentally crumpled up my birth plan and set it on fire. Pre-hospital me, armed with all the knowledge of someone who had never been in labor before, had ideas like I think I’ll be better off without an episiotomy or an epidural! and I’m pretty sure my boobs will make colostrum as soon as my womb puts up a “vacancy” sign! These are true for some people, but in my case, not so much. After having met so many midwives at doctors in the maternity ward, I was comfortable with my treatment and happy to hand most of the decisions over to them. (I’ll note though that even though I didn’t use my birth plan, I’m glad I bothered to write it. It was like an extra credit assignment that forced me to do more research about what happens during labor and delivery. Of course, if you have specific needs for your labor experience or concerns about your health care, no matter how big or small, you should tell your health care providers.)

After our meeting with the doctor, a midwife came in to tell us they often recommend that partners go home because it can take days for labor to start. I wouldn’t be allowed to wait longer than a day due to potential complications, but if Kåre went home, he could at least get one night of rest before, you know, possibly never getting a good night’s sleep again. He stayed with me though, out of the fear that if he went home to sleep on a real bed in his state of exhaustion, he’d stay asleep forever. Also because he didn’t want to miss anything. Also because I didn’t want him to go. He quickly fell asleep on the lounge-y chair next to my hospital bed.

I couldn’t fall asleep, so I spent my time walking back and forth down the hall to the drink cart for glasses of saft (fruit-flavor syrup mixed with water), going to the bathroom because I drank too much saft, attempting to write legibly in my baby journal with my pregnancy-induced carpal tunneled hands, wasting time on my phone, and asking myself important questions, like “Why aren’t there any good Pokemon in here?”

At some point my feet and ankles ballooned to a size I did not plan for. I don’t know exactly when this happened, just that I managed to avoid this kind of swelling my whole pregnancy until I was stuck at the hospital with slippers that no longer fit. One of the only tips I have to give first-time pregnant peeps is to make sure your hospital go-bag includes slippers that are extra-roomy or adjustable. I spent most of my hospital stay shuffling around with mildly squozen feet. “Squozen” may not be a “real word”, but “squoze” is good enough for Merriam-Webster, so it’s close enough, dammit.

Around dinner time, Kåre and I ventured upstairs to the patient canteen. Next to a modest dining room was a smaller room with beverages and a mini buffet-style line whose contents changed depending on the meal time. Dinner that night was some kind of Asian-esque sweet-and-sour chicken and rice thing. If you told me it was produced in the same industrial kitchen that makes economy-class airplane food, I wouldn’t have questioned you. Having said that, I kind of love airplane food and, not to brag or anything, but I’m severely non-discerning when it comes to any pairing of saucy food and rice. This seems like a good time to remind you that I used to work at a food website. Full-time! In the past tense. (Lest I appear ungrateful for the hospital food, I am totally grateful for having free, unlimited food on top of my super low-cost, unlimited healthcare. And if getting better healthcare requires sacrifices in the kitchen, that’s fine with me.)

My sad-looking plate is brought to you by…me. I could’ve taken as much food as I wanted, yet I opted for a partially filled plate accompanied by one piece of crispbread and a wee tub of jam. I think I just had no idea that I needed truckloads of energy for what was to come. So, tasked with gathering the building blocks of a pre-labor diet, I collected a bundle of twigs and called it a day.

Over the evening, I mostly wasted time on my phone, wrote in my journal, drank saft, and continued having Braxton Hicks contractions instead of the real deal, all while dribbling amniotic fluid. (Shout-out to the workers who kept the bathroom’s endless supply of incontinence pads endless: You were really there for me.)

Around 9 p.m., I went back to the canteen to grab kvelds, the evening Norwegian meal that comes after an early dinner. The choices were nearly the same as breakfast: various breads and pålegg. I made up for my meager dinner plate with a few slices of whole grain-ish bread, three pats of butter, leverpostei (liver pate), cucumber, cheese, and ham. Kåre had grabbed a sandwich and coffee from the Deli de Luca in the lobby, as well as a big cookie for me.

An hour later, a midwife came in to check on us. We were surprised when she told us the ward was full. The halls were quiet—there were no screams of labor nor sight of midwives stretched thin. But the midwife assured us it was a full house of women like me who hadn’t gone into the throes of labor yet. That explained the calmness: the screams were yet to come.

I asked the midwife if we could listen to the baby’s heartbeat. I had spent the last nine-ish months worrying that something could’ve gone wrong without me realizing it, so why stop now? When the midwife’s doppler amplified Tilda’s perfectly normal heartbeat, my worry lay back in its chair while wiping the sweat from its brow. Then the midwife told me she had to chase Tilda’s heartbeat with her doppler because Tilda was moving around so much. And the sweats returned. While I was happy to hear that Tilda was itching to leave her uterine prison, I was a little disturbed that I didn’t feel her movements. How could I miss the fetal equivalent of a captive trying to wrestle their way out of a locked trunk? What else was I missing? Where was my connection to Tilda? Would I lack mother’s intuition for THE REST OF MY LIFE? DID I FAIL ALREADY OH GAWD

Nah it’s all fine.

The midwife told me that if I had trouble sleeping, I should ask for sleeping pills. That night might be my last chance to get a decent amount of sleep, after all. Luckily, all the not-napping I did earlier made me fall asleep without a problem.

Contractions begin: 14 hours until birth

Around 2:30 am, a feeling of mild period cramps woke me up. I ignored the cramps and continued sleeping. It’s not like I was in labor or anything. An hour later, my brain remembered that I was in a birth ward and sputtered, “Uhhh…am I in labor?” I Googled something like “labor period cramps” and wondered how I should note the timing of my contractions—should I stare at my watch and count the minutes?…with my buuuh…rain?…brain?—and then I remembered it was the 21st century and I had a tiny computer in my hand that could do pretty much anything I wanted by connecting to other computers through the air. So I downloaded a contraction-timing app. Each cramp was ten to 20 minutes apart, lasting about a minute each time. It wasn’t painful yet, but now my brain was too distracted to go back to sleep.

I pulled the call string and a new midwife came to check on me. While feeling my belly, she thought Tilda may have rotated!… but a quick ultrasound showed that Tilda was still destined to come out butt-first. The midwife told me there wasn’t much to do besides relax until the contractions became more painful and frequent. She was right, but it’s not easy to forget that you’re confined to a slow cooker full of pain broth. Right now it’s just a lil’ warm, but eventually you’ll be boiled alive. It’s gonna hurt in ways you’ve never imagined. Anyway, you won’t reach boiling point for several hours. Or more. Or less. Nobody knows.

Over the next three hours or so, my contractions became more painful, but they still remained in the territory of “bad period cramps” and not “jagged shard repeatedly stabbing my will to live.”

At around 7 a.m., I was hit with a more intense contraction, followed by a full-body shiver and the urge to swallow my spit. Then I bolted upright and puked on the floor. And a bit on my pants. And a bit on my right foot. And a bit on my right slipper. It happened so fast that I didn’t even have time to feel nauseous. I just sat there surprised and confused.

We called for a midwife. She helped Kåre clean up the mess as I sat dazed over the side of my bed. I felt bad for the midwife even though wiping up a few splats of puke probably rated very low on the scale of gross bodily fluids she faced each day.

I put on a clean pair of pants from my go-bag and grabbed a hospital gown from the supply cabinet. As soon as I put on the gown, I felt stupid for not wearing hospital gowns from the start. They’re hella comfy. And it was one less piece of laundry for me to worry about. I could just pop on a fresh gown whenever I needed it and toss it in the hamper when I was done.

Two hours later at around 9 a.m., another midwife came in to monitor Tilda’s heart rate, as well as mine. Everything looked normal. Unlike earlier when I felt nothing from Tilda, this time I could feel her movements more clearly thanks to the pressure of the straps around my belly amplifying Tilda’s movements. And dang, was she moving. If the fluid I had been living in for months was draining out and I was surrounded by a muscle that was repeatedly smushing me like a malfunctioning garbage compactor, I guess I’d be antsy, too. I wanted to get her out of there, but that wouldn’t happen for another nine hours or so.

At this point, my contractions were at a painful “intense period cramp” level and sometimes accompanied by uncontrollable shakes, but they weren’t painful enough to keep me from taking notes on my phone. Brain function was still normal. The will to live, if not healthy, at least existed. But with each contraction I could feel my inner battery depleting, and the five to ten minutes of rest in between wasn’t enough to recharge. This worried me because I knew I was going to feel much, much worse, and for an unpredictable length of time. Before I went into labor, I was afraid of getting an epidural. Now the prospect of getting a needle stuck in my back and flushing my spine with sweet, sweet druggos was the only thing I had to live for. I mean, besides having a baby.

I continued trying to eat the breakfast a midwife had brought me earlier: a banana, half an apple, four slices of bread, butter, cheese, and crackers, as well as a small pitcher of orange juice. My appetite took a nosedive after I puked, but knowing I’d need the energy later, I shoved something into my belly.

Around 1 p.m., I woke up to take more notes. Or rather, a particularly painful contraction woke me up and I couldn’t fall back asleep. I had already woken up multiple times from less painful contractions, but I managed to sleep through enough contractions to feel somewhat rested. Sensing that the boiling point was near, I went to the bathroom for the last comfortable potty break I’d have before giving birth. (Little did I know, this would also be my last comfortable poop for over a week. Trying to poop after giving birth is terrible.)

After that note-taking session, I didn’t write any more notes. Particularly painful contractions turned into something worse. Thank god I took that bathroom break because now no part of me wanted to leave my bed. Those minor period cramps from 12 hours ago were a distant memory, replaced by contractions that felt like an impossibly immense amount of pressure that the human body shouldn’t be capable of. My contractions were either trying to compress my uterus into a black hole or expel all of my innards. I tried to remind my body that organs stay in, baby goes out. My body didn’t listen. The squeezing was automatic, and I was just a fuel tank supplying the energy.

A bunch of stuff happened in the next five-and-a-half hours before Tilda popped out around 6:30 p.m.. I don’t remember everything nor what time any of it happened, so here’s what I do remember, the worst “Best Of” hits.

I puked again. At least this time I was prepared. I used a barf bag that a midwife had prepped for me after my first puke. The barf bag was a long plastic bag with a sturdy ring around the opening, great for sticking your face in and ensuring no puke would escape. It worked! The floor and my feet were spared of more bodily fluids.

I knew the enema was coming, but as my contractions got worse, I couldn’t see how I was going to get through it. I also couldn’t see much by choice because I was too tired to prop my eyelids open any wider than the necessary height of “pupil”. Leaving my bed felt impossible. But thanks to the most gentle, persuasive, and patient midwife who was tasked with giving me the enema, I pulled myself out of bed and flopped onto a rolling walker that featured handles and cushions for resting my arms on. I also rested my head on the cushions as I thought about how I wanted to die. I could barely kept my head up while shuffling down the hall, flanked by Kåre and the midwife, to the larger bathroom in the back of the midwives’ office.

For the midwife to administer the enema, aka squeeze a bottle of stuff up my anus, I had to hoist myself up on an elevated table. I don’t know how I got up there, but I’m guessing it took a lot of help from the midwife and Kåre. After the midwife emptied the bottle into my butt, I had to lie there for another 10 minutes or so to let the liquid snake around my inner tubes. And by “lie there” I mean “focus my driblets of energy on not pooping right there on the table.” After enough time had passed, the midwife and Kåre helped me shuffle to the neighboring toilet stall. Kåre joined me in the stall by my side as the midwife stayed out by the open stall door, ready to help in any way. And then we waited. It seemed that my earlier poop break had already drained my colon. But every contraction made me feel like pooping, even if there wasn’t much left to poop.

Having painful late stage contractions while sitting on a toilet and feeling like you’ll never stop pooping and yet you somehow have to clean your butt and stop pooping and hoist up your incontinence pad-lined mesh underwear and make your way back to your hospital bed which isn’t that far away but is definitely TOO FAR AWAY is such a unique mix of terrible feelings. At least there wasn’t anything painful about the enema itself. I felt so lucky to have the nicest midwife ever, as well as Kåre, reminding me how to breathe, because breathing while in labor is not the same as the good ol’ everyday breathing I had been doing my whole life. They told me to breathe deeply through my contractions, all the way down to Tilda, to straighten my back and loosen my shoulders, to drop my weight into my waist. I could do maybe two of those things at once, knowledge that I immediately forgot until I was coached again during the next contraction.

I rewarded the midwife’s excellent coaching and bedside manner by spending too much time on the toilet. She reminded me multiple times that I had to get back in my hospital bed and strapped back into the EFM as soon as possible, but I didn’t feel like I could leave the toilet. I was having contractions every couple of minutes by this point, meaning that by the time I thought I was done pooping and had wiped myself clean, another contraction would bust through like the Kool-Aid Man brandishing a sloshing pitcher of poop. I rewarded Kåre by crushing his finger bones to dust every time I squeezed his hand to channel my contraction pain away from me.

After I felt like my colon was as empty as it was going to get, Kåre and the midwife helped me hoist myself back onto the walker and do a geriatric shuffle back to my room. Lying in my bed strapped into the transducers, eyelids mostly shut, all I could think about was that epidural. Like… where was it? Why didn’t I get it already? Why wasn’t I getting it right at that moment? WHERE DAT SPINE POKEY? The midwife told me it would be another 15 minutes or so, which felt like an impossibly long time because by that point I’d surely faint or the baby would pop out.

The arrival of the anesthesiologist was the greatest source of relief I had felt in a while. And then my relief got stomped on by that giant Monty Python foot when I remembered that I’d have to stay still as he poked a fat, hollow needle between my spine bones. Stay still when I was having contractions what felt like every minute? H…how? At least I was allowed to simply roll onto my left side instead of having to sit upright like I was told earlier. I didn’t think I could muster the energy to pull my body up when I could barely open my eyes.

Even though I felt like a tranquilized half-zombie by this point, I could comprehend what everyone was saying just fine and do whatever I was told. (Forming comprehensible words was a different matter. I wasn’t saying much by this point besides moaning pitifully every time a contraction hit me.) The anesthesiologist, whom I’ll call Dr. Pokey because I didn’t get his real name, gave me clear, short directions that made me feel as much at ease as I could’ve in that situation. His instruction to keep me stable through multiple contractions was to push my spine against his finger whenever he told me to. That’s all it takes to aim a needle into my spine? Oh. It sounded too simple to work and, at the same time, too difficult for me to do. As I predicted, I couldn’t stay totally still—I was breathing in and out as though I were hyperventilating, my chest heaving with every breath—but I managed to stay still enough. The first thing I felt was Dr. Pokey giving me a shot of anesthetic to numb the area where he would insert a bigger needle carrying the catheter. After that small prick, I didn’t feel much else. Nothing painful, at least. I heard a constant rustling of things behind me, but can’t remember feeling anything until a cooling sensation trickled down my back, like my spine took a swig of menthol. After that, I vaguely remember feeling large strips of tape being stuck to my back. It wasn’t until long after delivery that I noticed a tube was stuck into my back. I was legit confused when Dr. Pokey was done and left the room because I couldn’t tell what had happened. He… donezo? He’s gone? But I didn’t even say goodbye.

And then I waited for the magic to happen. For all the pain to go away. To feel nothing. But in a good way. I obviously hadn’t done enough research because I thought getting an epidural would work as quickly as flipping a light switch. The pain relief can take 15 minutes to kick in, if all goes well. If mine took 15 minutes to start working, it felt like a very long 15 minutes.

After a few midwives flopped my legs onto the stirrups at the foot of my bed (my thoughts as I watched them do this: leg go there, other leg go there, me sleepy), two doctors came in to check how far my cervix had dilated. This entails someone pushing their fingers up your vagina to your cervix and rooting ‘em around as through they’re trying to scoop up the last dregs of peanut butter at the bottom of a jar using a butter knife. How does it feel? SHARP ‘N JABBY. It did for me, at least. Admittedly, that’s not much compared to the pain of contractions.

I don’t know how much my cervix was dilated by that point. All I know is that it was farther along than the doctors expected. Something about my stats gave them the false impression that I had more time before I had to start pushing. While checking my cervix, one of the doctors said something like, “Yup, it’s time, I see a butt,” but definitely not those words because they would’ve been speaking in Norwegian. Kåre probably relayed the info to me as I was squeezing the functionality out of his finger joints. My physical reaction to the realization that a butt was in view couldn’t have been much more than barely cracking open my eyelids and squeezing out a weak “wuhhht?”, but my internal reaction was more like WTF TOO SOON, THE DRUGS AREN’T DRUGGING YET.

After being told that go-time was near, the doctors attached an electrode to Tilda’s butt to better monitor her heart rate. Cue more of the aforementioned “get dat peanut butter” action, except further down the jar. [Insert Mr. Burns-like shudder.] It wasn’t as bad as contractions, but it was still shitty. I just continued clenching my eyes and face and anything else that could be clenched until Tilda was hooked up.

Around this time, a midwife drained my bladder using a catheter. I don’t remember much about this process besides a brief sharp sensation—say, the feeling of a very thin tube being stuck into one’s urethra—and then peeing uncontrollably. Not that much came out since I had barely drank anything after the first puke.

When it was time for me to push, I kept my eyes closed half the time in an attempt to conserve the tiniest droplets of the energy I barely had. The doctors and midwives kept their commands short and clear. “Push!” (This was easy. Pushing was all felt like doing during each contraction.) “Don’t let the air escape as you breathe!” (I kept making sad deflating-balloon-like noises until I tried harder to keep the air in, making me feel like my head was going to burst.) “Take a break!” (Aka unclench all the things and turn into a jelly-filled flesh bag for a minute.) “Next contraction, one more push!” (Probably not just one more push.) “Breathe!” (Oh yeah, breathing is important.)

Although the contractions still hurt, they didn’t hurt as much as before. The feeling of “these contractions are trying to kill me from the inside” was replaced by “these contractions are actually helping me do the thing they’re supposed to do!” Each push felt like progress that was worth the pain. I don’t remember pain from a baby popping out of me, just…sensations. Like when someone told me Tilda’s butt was out, I thought, oh, that’s that thing I felt. I could also feel it when one of the doctors made the cut for the episiotomy, but it didn’t hurt. Later I was told that they also used forceps, something I hadn’t noticed at all. Squeezing out Tilda, thought not easy, wasn’t as painful as I was afraid it would be considering how quickly things progressed. Thanks, awesome doctors and midwives! Also, thanks, epidural! Let’s never not get that again.

I’m guessing that from first push to the last took less than half an hour, but I honestly don’t know. All I can say for sure is that it felt very fast compared to everything that happened before. When the doctors said Tilda was out, I was surprised it was already over. I can’t imagine how it would feel to be stuck in push-mode for hours.

When Tilda popped out, she was pretty quiet. It was not the onslaught of piercing wails I expected. Kåre cut the cord soon after that. Once upon a time I thought Tilda should be plopped right on top of my chest after being delivered, and cutting the cord should be delayed for as long as possible. In reality, I was in no state to enjoy a baby straight from the oven. I had no problem with the quip snip and the midwives whisking Tilda away ASAP so they could weigh her and clean her up.

It wasn’t long before someone plopped Tilda on my chest, a scrawny, wriggling five pounds of rosy flesh and semi-fused bones adorned with nothing besides a tiny pink knitted cap and a name tag. I did it! I made a whole-ass human! It was one of the biggest accomplishments of my life!…and yet I remember almost nothing about these first few moments with Tilda. I think it’s because nothing really “happened”, in a sense. The trauma chisel that had been nicking my brain the last too many hours suddenly remembered it left the stove on or something. No longer did I have to worry about how Tilda was doing inside me, nor dread waves of painful contractions. And I was too tired to worry about future trifles such as how do I change a diaper? Or feed a baby? All I had to do in my exhaustion- and relief-flooded state was lie in bed and cuddle Tilda. The cutest lil’ man-alien-baby nugget I ever did see.

I said I remember almost nothing. Three things I do remember from those first few moments with Tilda:

- Baby skin is the softest skin in the history of skin.

- Her nails are so long! How do I clip ‘em without chopping her fingers off? (Answer: I bit them off.)

- She’s gonna be an only child because I do not want to go through labor again. (Update: Years later, I think about having another baby like, uh, every day.)

Not long after I popped out Tilda, the doctors told me it was time to deliver the placenta. Moments later, I gave birth to what felt like a soft blob. It took hardly any effort. By the way, the placenta is COOL AS HELL and everyone should listen to the Radiolab episode “Everybody’s Got One” to learn the extent of its coolness. After listening to that episode, I feel like I should’ve said hi to the placenta before it was taken away and thanked it for keeping Tilda healthy. Later in the week when I was in the post-natal ward, another new mom told me it took ages to get her placenta out. I forget the exact time but all you need to know is that it was horrifyingly long and I’m glad my brain threw out the actual length of time. Delivering a placenta is usually easy, but like everything related to labor, there are huge variations.

My magical/confusing/hazy first moments in fresh baby bliss came to an end when it was time to get my bits sutured. As far as I can tell from looking at too many diagrams, I got a second degree episiotomy in which the doctors made a cut from my vagina and veered into the left side of my inner buttcheek. I didn’t feel pain when they made the cut, but I sure felt it when they sewed me back up. It was the stitches in the meatiest part of my butt that hurt the most. My protests and wincing earned me a shot of local anesthesia in that area, which helped a bit but not as much as I preferred. And unlike delivery, which felt unbelievably fast, getting stitched up felt like the opposite, even though it may have been faster. Seeing as I was just lying there as opposed to actively doing something, my mind didn’t have much to focus on besides ouch, needle string being pulled through my flesh, ouch needle, string again. Of course, I’m grateful the doctor—the same one who instilled me with confidence shortly after I was admitted to the delivery room—took her time to carefully realign my skin to almost good as new. Later when I was back home, I used a mirror to see how the stitches were healing up and all I remember thinking was dang, those stitches look like they were done with a sewing machine.

I was so relieved when the stitching was finished. But there was one more step: checking my vagina and anus to make sure the muscles were okay after stitching. And thus I bring back our peanut butter jar’s old friend, Lil’ Knifey, whom I would’ve been happy to leave in the cutlery drawer until the sun consumes the earth. One of the doctors rooted around my vagina and anus with their finger until they were satisfied that all was good. I had to remind myself that the brief but sharp pain was for a good cause. I definitely wanted my butt to work.

During the next few hours, Kåre and I didn’t have to do much besides chill out with Tilda and start recuperating. Thankfully a midwife brought us a tray of food, mostly fruit and bread, to remind us that we should eat something. The food was for Kåre, too—if there’s ever a time that the mother’s partner deserves free food, this is it. At some point Kåre’s parents came in to say a quick congrats and get a glimpse of Tilda. They definitely deserved a first look for all the help they gave us. I imagine that I mostly looked tired and out of it, but I was happy to have such eager family support.

Near the end of the evening, a young student midwife was tasked with cleaning up the area around my episiotomy and draining my bladder. Since she was still a student, my vaginal breech birth was probably a valuable learning experience, but I felt like she drew the shortest of all straws having to do the dirty work of cleaning the war zone and giving me one final cath. (There was hardly any urine to drain. I kept forgetting to hydrate.) While she was staring into my crotch, gently washing away the horrors with warm water and dabbing the area with paper towels, I asked her if she had found her calling. She said yes. Then I asked her if she wanted kids considering what she witnesses on a regular basis. She said… sometimes.

The midwife gave me a frozen maxi pad to add to my first post-delivery mesh underwear arsenal, which included two incontinence pads under the frozen pad. The amniotic fluid may have stopped dripping, but you know what comes next? Lochia! You leak blood and various uterine sheddings for up to six weeks. Just the icing on top of a cake layered with a stitched perineum and constipation and general full-body aching and extreme sleep deficiency and breast-feeding boot camp.

Sometime around midnight, it was time to leave the delivery ward where I had been for nearly 36 hours and head up to barsel, the post-natal ward, on the second floor. The student midwife and another midwife swiftly tidied up the room, gathering laundry and tossing out garbage. Then they grabbed whatever bags and drink pitchers that Kåre couldn’t carry. They said they’d push me on a wheelchair and take the elevator up, but in my rejuvenated state—no more contractions! Eyelids open wider than pupil-height! Sugar in my bloodstream!—I told them walking would be more comfortable than sitting on my freshly stitched and aching butt. And it would’ve been, if when I stepped out the door my head hadn’t been immediately squeezed by invisible earmuffs, dampening all sound. Overcome with dizziness, I could barely stand up straight. Oops. I guess pushing out a baby gave me a dose of overconfidence. I felt like I could do anything, but I couldn’t even walk without help.

So wheelchair it was. I propped myself up on my hands in an attempt to hover over the seat and minimize pressure on my butt. Every time the wheelchair made the slightest bounce traversing a door frame or going in and out of the elevator, I took a sharp breath. Thankfully, it was a short ride.

And then I was in my new home for the next four days. As all the family rooms were occupied, Kåre had to go home while I shared a room with up to three other new mothers. I was disappointed, but I wasn’t surprised considering the delivery ward had been full. Kåre also needed quality sleep without having to tend to me or a new baby. And I needed a crash course in How To Keep Baby Alive. And I got it. Coming up in my next post that I may or may not ever write. (If you want me to write it, leave a comment! I respond to public pressure!)

Bonus section!

Finally, you’ve reached the end of this post! Thanks! I figured I should give you a little update because the tiny nugget I showed you earlier in the post is now an over two-and-a-half-year-old bundle of kinetic energy. Except in the mornings when she is often a groggy lump. (Just like her mom and dad, Tilda is not a morning person.)

As far as we can tell, Tilda is a normal toddler. She loves singing (did you know the “Let It Go” obsession starts this early? I did not). And she’s obsessed with excavators and dump trucks. And she says hi to all dogs. And she freaks out over donuts, especially if they’re pink. And she throws tantrums at random times and then recovers quickly for random reasons. We just gotta keep this going for…[checks calendar]…the rest of her life and she’ll be fine.

Comments